This article originally appeared in the December 2021/January 2022 issue of Dream of Italy. Members receive access to more than 180 back issues—if you’re not a member, join here.

Though a beloved city of art, Venice has always been in a precarious position when it comes to preserving its treasures. The city simultaneously suffers from the fate of being built as a series of islands on an oceanic lagoon and bears the effects of flooding, humidity and saltwater that threaten precious art and architecture. With so many masterpieces, and so much constant maintenance needed, conservationists have their work cut out for them in La Serenissima. For the past 50 years, conservation organization Save Venice has stepped up to answer the call.

Though Venice floods seasonally due to acqua alta (high water), the water typically recedes within days, remains at a fairly low level (despite its name) and does not cause much damage or disruption. However, the floods can sometimes be catastrophic, the most infamous occurring in November 1966, leaving the city under six feet of water and trapping residents in their homes for 24 hours.

“The floods of 1966 brought the world’s attention to the fragile nature of the artistic patrimony here. There was an appeal initially by UNESCO that anyone who’d been inspired by Venice—art historians, musicians, writers or even tourists—should try to get together and give something back,” says Melissa Conn, director of the Venice office of Save Venice.

In the aftermath, experienced art restorers came from Florence—which also had its own epic flood in November 1966—to help clean up Venice. Those restorers formed conservation committees that eventually became Save Venice in 1971.

“Our mission is to promote and protect the artistic patrimony, so that can be restoring a building or painting or sculpture, or promoting exhibitions, publications, works of art, archives and fellowships for students who are working on topics of Venetian art,” says Conn.

Conservation Techniques and Projects

Modern technology has led to advancements not only in the techniques of the restoration process, but also in the methods used to examine art and determine its origins, conservation needs and history. Infrared photography and ultraviolet imaging help restorers see beneath the surface of the paint and understand what they need to remove, clean and repair.

Many artworks have been previously restored, but those earlier restorers likely did not have the same tools and understanding of how to best preserve the pieces, nor the proper paints and pigments to replicate the original color palettes. Meanwhile, architecture requires constant maintenance, especially given the humid climate and seafront location.

With a team of experts such as art historians and artists at hand, Save Venice works on restoring 40 to 60 projects at a time, whether on site around the city or in its restoration lab. Some of the more noteworthy projects they have tackled—all of which you can visit for yourself next time you’re in the city —can be found at the Church of San Sebastiano, the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta on Torcello and the Church of Santa Maria and San Donato.

In restoring the 16th-century Church of San Sebastiano, Save Venice focused on Paolo Veronese’s wall and ceiling frescoes as well as oil paintings on wood and canvas. Conservators stripped yellowed varnish and excess paint from the massive ceiling frescoes illustrating the story of Esther from the Old Testament to restore Veronese’s original color palette and protect the wooden frames surrounding the paintings.

The team also took measures to prevent humidity and saltwater—two natural enemies of art conservation prevalent in the Venice lagoon—from entering San Sebastiano by treating the porous brick walls and façade, weatherizing windows and installing new flood barriers.

At the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta on the island of Torcello, conservationists worked simultaneously on restoring more than 2,400 square feet of Byzantine mosaics and strengthening the brickwork behind the mosaics to ensure the walls of the church could support the weight of thousands of tiny tesserae. Where mosaic pieces had been lost, the area was filled in with paint so that the gaps are not visible from a distance.

During the restoration process on Torcello, workers discovered never-before-seen and previously unknown frescoes from the ninth century, painted in a Carolingian decorative style and depicting the Virgin Mary and Saint Martin. These frescoes were eventually covered over by the mosaics, and prove that the church attracted Western European artistic styles alongside Byzantine art.

History of Art Patronage

The roots of modern conservation sponsorship extend back to the era of art patronage, which was prevalent in Venice. Unlike Florence and other cities dominated by noble families like the Medici, Venice was a city of elected officials and merchants who earned their wealth from professions such as shipping, trade and navigation.

During the Renaissance, the Venetian Republic government commissioned art to showcase the city’s culture to foreign traders coming to buy silk or spices, or to diplomats visiting on government business. As a result, even the most obscure, off-the-beaten-path churches have art by great masters like Titian.

“Certain artists were promoted by particular noble families, who would want that artist to decorate their chapel in a certain church. There were also private collections that now have become part of the state museums or the city museums. The Venetian Republic commissioned artworks because Venice was the motherland and they had to show off. They wanted everyone to come here and be in awe. Venice was meant to shine, and you had to show the best of everything.” says Conn. “Now that we have the Biennale, Venice continues to be at the center of an artistic scene.”

Now, that support for the creation of art has turned into support of patronage for preservation. Sponsors are always needed to fund Save Venice’s work—individual works of art, buildings or parts of projects can be adopted for conservation—and the organization has made its name on fundraising for and restoring 1,672 works of art during its lifetime.

The projects highlighted in this article range from $3,000 for a group of three pastel portraits by female artists Rosalba Carriera and Marianna Carlevarijs, to up to $98,000 to fund the entire restoration of the iconostasis at the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta on Torcello.

The work a patron chooses usually comes down to a gut feeling. After serving on Save Venice’s Board of Directors and hosting events for almost two decades, Adelina Wong Ettelson wanted to take her involvement to the next level. She funded her first conservation project two years ago, a Tintoretto painting from 1578 called Mercury and the Three Graces that is currently on display in the Palazzo Ducale. Restoration work on the painting was completed in 2020, and she has since been able to see the finished work in person.

When she was deciding which painting to sponsor, she says, “Mercury and the Three Graces just spoke to me. There was something about the lines and the mood of it.

“To know that I was involved in helping restore this beautiful painting to its original glory was so exciting for me. I’ve never done anything like this,” she says. “It’s a natural evolvement of where I want to be with the organization and how I want to support it. I was definitely interested in the painting area, so I just had to wait for the right one that resonated with me.”

People Are the Backbone

Tina Walls, who first visited Venice on a trip in high school in 1971, was invited to become involved in Save Venice by a fellow art museum board member. Walls says one thing that she has in common with so many of those that volunteer with Save Venice is that she’s never forgotten first laying eyes on Venice and wants to preserve that experience for generations to come. Now the president of Save Venice’s Board of Directors, she says, “I was immediately impressed with the projects, the supporters’ passion for Venice and Venetian art and culture, and the sense of shared community.” She attended her first Carnevale gala in Venice in 2008 and has since participated in several balls, galas and trips with the organization.

Wong Ettelson was initially drawn to Save Venice for the social aspects of the organization. She became the chair of the Young Friends of Save Venice committee for members under 35 years old, then joined the Board of Directors 10 years ago. She is now the chair of the events committee on the Board of Directors, planning the organization’s balls and galas, which are the organization’s major fundraisers.

Wong Ettelson’s favorite events are ones hosted in private homes in Venice that enable guests to see how Venetians live. “I think that’s really what traveling and exploring is all about—to understand. It goes back to the people and the connections. Every one of us wants to see more behind the scenes, or what it feels like getting to go see San Sebastiano and understanding what it actually takes to restore all the beautiful tiles and the entire church,” she says. “That was what the Venetians did in the old days when they asked an artist to do an entire church or entire building.”

Anniversary Celebrations

As Save Venice completes its first half-century—a milestone that coincides with the city’s 1600th birthday—the organization is focusing on Venetian women in art by both restoring their artworks and researching their lives. During the Renaissance, Venetian women painted, wrote poetry and pursued other artistic exploits, but few of them have been recognized or studied and little is known about them. Many worked alongside their fathers or brothers in art workshops, but when the women married, they often left their artistic pursuits behind. Some, however, continued to paint and took over the workshops after their fathers’ deaths.

Among these female artists is painter, poet and scholar Giulia Lama. She studied under her father, Agostino, and continued to paint after his death in 1714. Her oldest known pieces were created in the 1720s, when she was almost 40 years old.

Lama’s oil painting Female Saint in Glory, currently in need of restoration, hangs in the Church of Santa Maria Assunta on the island of Malamocco and dates to the 18th century. Its surface is currently covered in pigeon droppings, discolored varnish and cobwebs, while the original paint itself is buckling. A previous restoration used paint that was darker in color than the original paint, covering the bright color palette and small details.

Two other artists spotlighted in the campaign are Rosalba Carriera and Marianna Carlevarijs, whose 18th-century pastel portraits will also be preserved. This work will focus on the frames, glass and mattes, including photographing the works and remounting them with acid-free materials to protect them for the future.

Native Venetian Carriera began her career painting miniature scenes on the lids of snuff boxes and later became one of the first artists to use pastels for portraits. A self-taught painter, she took commissions from European nobility, diplomats and Venetian court ladies for portraits. Carlevarijs, whose father was also an artist, studied under Carriera and adopted a similar style to her mentor.

Save Venice’s anniversary campaign capitalizes on growing interest in these women. In recent years, papers presented at the Renaissance Society of America conference have focused on female artists, spurring momentum for scholars to more heavily research women’s influence in Renaissance art. Sponsors can adopt a painting by one of these women or contribute to research that will create a database of women artists in Venice and their accomplishments.

Save Venice Membership

Though Save Venice welcomes sponsors, another way to support the organization is by becoming an annual member and joining local chapters throughout the U.S. Memberships start at $100 per year, and members receive swag like a tote bag and newsletter, access to live virtual art lectures, invitations to weekend excursions in the U.S. and exclusive one-hour conservation tours by Conn and her colleagues to see restoration work up close (sponsors can also, of course, visit the pieces they’ve sponsored in person).

The tour takes members behind the scenes to a Save Venice conservation site in Venice where they learn about conservation techniques. For example, in the Church of San Sebastiano, members learn about Save Venice‘s campaign to restore Veronese’s paintings and frescoes and visit the elevated monks’ loft that is not open to the public. Sometimes there is a chance to interact directly with a restorer, although this is not always possible.

“It’s very much a hands-on individual tour. I tell you about the conservation behind the scenes, and it’s a very special experience,” says Conn.

With the shift toward virtual events due to the pandemic, Save Venice is organizing more online art history and conservation lectures for members. The lectures are given by art historians, specialists and experts and provide a great introduction to Save Venice for new members. “Because they’re so passionate, they really make it fun to listen to,” says Wong Ettelson.

Both sponsors and members receive invitations to exclusive, high-profile events hosted by Save Venice. Pandemic conditions permitting, the annual black-tie Masquerade Ball in New York takes place in April, bringing in more than $1 million in donations and sponsorships as well as attracting new members and press coverage. Wong Ettelson explains that the ball is seen in the fashion world as a “mini-Met,” referring to the Met Gala hosted by Vogue’s Anna Wintour. (The ball was not held during the pandemic but will return to New York in April 2022. Ticket prices for past balls have started at $1,500, of which all but $300 supports Save Venice directly.)

Another large event is the biannual gala held in Venice. The four-day event includes visits to the restoration sites, tours and lectures in museums. In the past, Save Venice has hosted smaller events before the ball in conjunction with sponsors such as Dolce & Gabbana. The gala is a more intimate experience, with about 100 to 150 people, while the Masquerade Ball hosts around 500. The members-only 50th anniversary gala will be held in Venice in October 2022; the cost for past galas has been around $6,000, including a tax-deductible donation to Save Venice starting at $2,250.

“It’s not just one piece of art. It’s revelations through having these private moments where it’s not the standard tourist spiel, and you’re getting to have experts and people who know exactly what they’re talking about in a very nice, private setting,” says Wong Ettelson of attending these private events.

Further, for those who are in Venice and want to contribute on a small scale, Save Venice organizes treasure hunts around the city that cost between $20 and $30. A popular treasure hunt for children involves searching for unique doorknobs, while others require participants to listen to the sounds of Venice or visit many of the works restored by Save Venice.

Other 50th anniversary celebrations include 50 celebrations around the world until March 2022, including dinners with experts. Donors can host a “50 for 50” event at a venue of their choosing by contributing between $5,000 and $100,000. All hosts will receive an event planning kit.

To join as a member or sponsor a piece, contact Kim Tamboer Manjarres, director of development, at kim@savevenice.org

Projects Awaiting Sponsorship

Currently, sponsors can adopt one of 12 apostles depicted on the iconostasis of the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta on Torcello, a rare example of artwork from Byzantine Venice. The Virgin Mary sits in the center of the wooden panel, with the 12 apostles surrounding her. The tempera paintings of each figure by Zanino di Pietro, dating to the 15th century, are set against a gold leaf background that matches the brilliant golden mosaics in the rest of the church.

Currently, the paint is flaking and some of the paintings have large holes where paint has been lost. The wooden panel will be removed and taken to a conservation lab in Venice, where restorers will clean it, reapply any salvageable flakes of original paint and fill in the gaps with new paint.

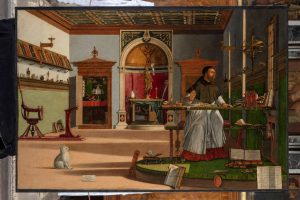

In addition, a narrative collection of nine paintings by Vittore Carpaccio is being restored in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (also known as the Scuola Dalmata), and two will be on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 2022. The Scuola Dalmata was established in 1451 as a confraternity for Venetians who were originally from the Dalmatia region of present-day Croatia. Between 1502 and 1508, Carpaccio was commissioned to paint a series narrating the stories of the Scuola Dalmata’s patron saints Jerome, George and Tryphon for its meeting house.

These paintings are affected by yellowing varnish and a more muted color palette that artists used during another restoration in the 1940s, obscuring the paintings’ original, more vivid colors. At the Scuola Dalmata, visitors will be able to see unrestored paintings alongside both restored paintings and photographic reproductions of works that are undergoing restoration. Sponsors can donate up to $78,000 toward this project.

How Save Venice Has Evolved

After 50 years, Save Venice remains true to its mission of responding to a city in need. With catastrophic flooding in 2019 came destruction to artwork and buildings all over Venice.

At that time, Conn organized volunteers to clean out churches, rinse tiled floors and do restoration and structural work. Save Venice launched its Immediate Response Fund, which raised $700,000 to provide quick aid to projects affected by natural disasters and requiring urgent conservation steps. One of its most monumental projects was the 5,300-square-foot mosaic floor in the Church of Santa Maria and San Donato on the island of Murano, which had been previously restored in the 1970s, as well as in 2012-2015, but was damaged again in the 2019 flood.

Walls says this project was especially meaningful to her, as it was the first project she sponsored, during the 2012-2015 restoration. “It was a passion project in honor of my father, who was a brick mason and highly creative with his designs for family and friends. I was impressed that the church’s priest kept the loose mosaics that had detached from the floor in recent years and that in the 2012-2015 restoration, they were used to maintain and conserve the work that had been completed after the previous conservation work in the 1970s,” she says.

The church’s especially low elevation on the island of Murano meant that the mosaic floor was submerged in seawater for several weeks and needed cleaning and repair. The restoration team also fixed holes in the walls where tidewater seeped in, removed rotting structural elements and restored mosaic tesserae.

During the pandemic, Save Venice continued its restoration work, but also provided a haven for academics. Expats working on their doctoral degrees were unable to access libraries to conduct research, write or study, so the organization opened its own Rosand Library to them. The library was donated by professor and Titian expert David Rosand, who left his personal collection of 6,000 books to Save Venice, and opened in 2015.

“Having the Rosand library and study center puts us on another level of not just conservation but also academics, working with the academic community and promoting scholarship,” says Conn.

—Kathy McCabe and Elaine Murphy