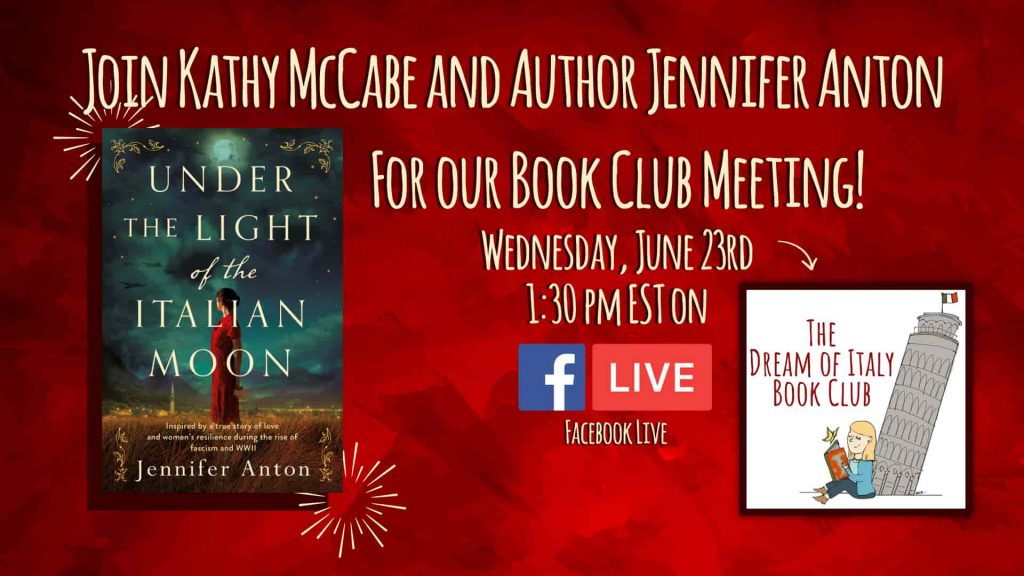

We will be joined by author Jennifer Anton on Facebook Live on Wednesday, June 23 to discuss her novel Under The Light of the Italian Moon. It is inspired by a true story of love and women’s resilience during the rise of fascism and WWII.

You can purchase a copy here but first enjoy an excerpt:

November 1914 Nina Argenta stared at the altar, trying to concentrate on the Mass since there was no chance of escape. The warm fragrance of incense surrounded her, and the priest’s recitations combined with the candlelit sanctuary made it hard to keep herself awake. It was Sunday, and like every Sunday of her ten years on Earth, she sat dutifully, bored by the teachings of the ancient text that is the Roman Catholic Holy Bible.

Under the vaulted ceiling of the Chiesa della Natività di Maria, the Madonna statue at the side of the church watched her. Candlelight illuminated the blue veil and gentle expression of the Blessed Virgin casting a shine, like polish, on one side of her face and leaving the other in shadow. Nina shivered, tugging her sweater around her shoulders. The yarn, thick under herfingertips, made her feel secure. It had been a gift from her mother on Nina’s birthday two weeks before – the birthday they shared.

“We are born on the cusp of two moons, passionate and loyal. A gift for my gift,” her mother had said when she gave Nina the present, blue to match her light eyes. It covered the once-white dress she wore that had belonged to her older sister. She leaned against the solid wood of the pew and studied the colours in the paintings of Frigimelica and Forabosco hanging on the grand church walls. Garments of rich burgundies like dried blood, sparkling golds, skin on a flat canvas painted to project luminescence and curve. It was easy to distract yourself from Mass when surrounded by such intricacy.

The women of her family sat to her right: seven of them in the row behind the nuns, a place of honour. The Argenta women occupied the same pew every Sunday. Onorina, four years her senior, perfect and pious, kept her eyes closed and prayed with a sparkling rosary threaded through her clasped hands, oblivious to the three youngest sisters who fretted next to their mother. Her father and younger brother, Vante, sat in front with the other men. Men in front, women in back, separated by the nuns. Nina’s older brother, Antonio, had not joined them today. At breakfast, tension had hung between him and their mother, which she assumed was why he missed Mass. The priest would surely notice. Mamma would be disappointed. Nina knew how it felt to let her down.

The chapel veil sitting atop her head slipped as she looked up at the imposing crucifix that stabbed down above the altar. Adjusting the lace, she missed a prayer response, causing her mother to look over with a lifted eyebrow. Adelasia Dalla Santa Argenta was not a woman to make angry, especially not during Mass. Her wooden spoon would be waiting at home to beat your culo if you weren’t good. She had a reputation for sternness not only with her family but with the entire town.

As the only trained midwife in Fonzaso and the villages surrounding, she had delivered every child Nina knew and had earned the nickname, La Capitana, The Captain. It was said even the priest feared her.

Nina could see her father, Corrado Argenta, through the heads and habits as he shifted from side to side. His eyelids drooped in boredom, but he glanced back from time to time to check on his wife and mother, both of whom he feared as much as the children did. Nonna Argenta, small and severe in her black dress and head covering, was the only one besides Onorina entirely consumed by the Mass. Nonna looks just like a strega, thought Nina, missing only a broom to fly away on.

Nina let out a relieved sigh when it was time for Communion. At last! Mass would be over soon, and she couldn’t wait to be by the fireplace, reading her book after helping Mamma and Nonna prepare the polenta for supper. She walked up the marble aisle, inching forward behind the nuns, then knelt at the altar and held out her tongue, awaiting the body of Christ. Receiving the wafer, she gave the sign of the cross and stood to head back to her seat. The taste of creamy paper stuck to the roof of her mouth and she contemplated why God would want children to have sore knees and numb bottoms to get into Heaven.

Passing rows of men knelt to pray after Communion, she saw the large Pante family filling two benches in the front of the church. Pietro, one of her sister’s classmates, leaned unceremoniously in the pew, trying to help his tiny brother fix his shoelaces, tied together so he would trip. A messy redhead crouched in the seat behind them was the likely culprit of the prank. The Pante boy finished helping his brother, then sat back on the pew, catching Nina’s eye and giving her a quiet smile. She hesitated before returning it. The Madonna was still watching her. I should be praying after receiving the body of Christ. She returned to her seat, then knelt again, bruised knees on cold wood, to await the end of the Mass.

“Fratelli e sorelle, ” Don Segala proclaimed after he had completed the liturgy. “I would like to ask for a special prayer today. Another group is leaving tomorrow for America. They will travel to Genoa and take a long ship ride. Signori, please join me here on the altar.” The pews squeaked, echoing in the church as a group of five men and three boys walked to the front. To Nina’s surprise, the Pante boy was one of them. Was it possible such a young boy was going on that voyage? There was an earnestness in the way he stood next to the other men who were a head taller than he was; his face was sombre. He stuck out a proud, lifted chin, smooth, unlike the others. A patched brown jacket, cut too wide, hung on his slender physique. I wonder how many brothers have worn that jacket before him.

The priest called out each of the men’s names. “Lord, please bless these men and give them a safe journey to America. Allow them to prosper there and, if it is your will, bring them safely home to their families here in Fonzaso.”

The parishioners united in an “Amen”. As Pietro returned to his seat, he peered back towards the Argenta pew, gave a wry smile, and nodded. Nina tried to see if he was looking at her or her sister, but Onorina was quick to bow her head again. The Madonna was watching her, too.

Nina knew many men were leaving Fonzaso to find work abroad. She had overheard her father mentioning it to her mother – the emigranti – but she never imagined such young people going. It unsettled her, and her heart raced as questions filled her head. Pietro Pante, who lived with his family a few streets down, who went to school with her sister, was leaving for America.

America!

The furthest she had travelled was to Padua with her mother, and Bergamo once. How exciting! What will happen to him? What would it be like to sail on a ship, miles away, to a new country? To start life over far away from Fonzaso? The Mass ended and the parishioners rose in song. Nina lent her voice with fervour and when she looked again at the Blessed Virgin, it seemed the Madonna was smiling at her.

After Don Segala and the altar boys completed the processional, the congregation advanced out of the church like a tiny parade. Organ music erupted from the doors, transforming into clustered conversations, and the piazza buzzed in dialect. As Nina skipped down the church steps into the autumn air, Mount Avena soared in front of her, rising majestically into the sky, its grey limestone cliffs slashed with zigzags of greenery. The November sun warmed her shoulders as she squinted at the peaks of the snow-capped Dolomiti, the pre-Alps, that hugged Fonzaso and split Italy from Austria.

Nina looked higher, past the church bell tolling over and over in the tower, and saw the little castle in the mountain, the Eremo di San Michele. On one of their walks foraging for mushrooms, her father had taught her that centuries before, the people built a chapel in the mountainside dedicated to Saint Michele, protector from evil. He told her they used to make houses of wood,and fires were frequent, so they installed a guardian to live next to the chapel in a caretaker’s house that looked like a miniature castle. The citizens paid him a self-imposed tax of one large bag of cornmeal each, and he ensured the bell alerted them to fires that could devastate the town. Nowadays, they built more buildings with stucco and stone, but the guardian remained in this place. Is he lonely? Nina wondered. Does he have his own Mass on the mountainside? Can he see me down here in the piazza? In school, the nuns said that the Eremo di San Michele, or San Micel as they often called it , was the only thing travellers going from the Trento or Vicenza provinces heading to Belluno could recall as they journeyed over the road called Paolina that the Romans had built. It comforted Nina to know that the man in the castle watched over them.

“So, you made it through Mass, Ninetta?” Papà came up behind her, speaking loudly above the rest of the chatter. The strength of his voice startled her, as usual, yet she couldn’t help but smile at him. Each word was a booming announcement when he was near other men and Mamma wasn’t around.

“Papà, you’re not going to America, are you?” Nina asked, squinting up at his big ears.

“America? No! I’m happy here in Fonzaso getting to see my Ninetta every day. Why, do you want me to go?” He poked her shoulder and tickled her neck.

Focused on getting her answer, she looked at him seriously. “Now they are sending children, aren’t they? The Pante boy, Pietro, he can’t be old enough to go off without his family. You wouldn’t send Antonio or Onorina, would you?”

A smile spread across his face and he teased, “Oh, it’s not me you want to go – you are dreaming of America!” Heads in the piazza turned at his pronouncement.

Before she could ask more, Teodosio Pante came to say hello. Corrado nodded a greeting. “Teo! I was just telling Ninetta about your boy heading to America.” He slapped the other man on the shoulder. “Why don’t you come by the house tonight for a drink? I’ve invited some of the others, too. We’ll toast them before they leave! I’ll give them a bit of my grappa to take with them.”

“Perfetto, ” Teodosio said. Patriarch of the massive Pante brood, father of fourteen, he had already sent one son to America. “Any excuse for your grappa is welcome. By the way,” he lowered his voice, “have you broken the news to Adelasia yet?”

Corrado bristled, glancing at Nina, then back to Teodosio.

“It’s fine,” he murmured, unusually quiet. “Come over tonight. In time, she’ll get used to the idea.”

“Used to what idea, Papà?” Nina asked, pausing from kicking a stone while she waited for them to finish. What does Mamma not know? It’s never good for her not to know something.

“Don’t worry, Ninetta,” Corrado tried to calm her. “Everything will be fine.”

Nina turned to see Mamma exiting the church last, along with the priest and nuns. She appeared as solid as her reputation in a grey dress that covered her completely from her broad neck to her strong ankles; she was twice the size of Papà. Her mother, Don Segala and the nuns stood talking on the steps of the church; they had important matters to discuss, always.

Nina and Corrado made their way around to greet the Corsos and Ceccons. The men smiled and patted Corrado’s back, asking him about his work in the sawmill, challenging him to games of bocce, and inviting him to the taverna for beer.

Nina greeted her school friends, and the children chased each other around the piazza, relieved to be released from the confines of the church. Soon the sun dipped, the chill deepened and the families of Fonzaso made their way through the winding streets to terracotta-topped houses with fires burning inside. Nina looked up at San Micel once more and felt the guardian watching as the people dispersed into tiny streets and alleyways. Joined by Adelasia, the Argenta family made their way to the Via Calzen.

The cobbles fanned out like a carpet of shells beneath their footsteps as they walked home from church. Smoke from burning leaves and chimneys wafted into the mountain air as they passed the houses of the Corsos and Bofs, neighbours since before the Risorgimento. Although Nina was aware of Vante’s excited chatter next to her, she found herself distracted by thoughts ofAmerica, ships on the ocean. What do they eat in America? It’s so far away, it’s another world. Soon the family approached their two-storey stucco house, the balcony pushing from the front casting a shadow in the midday sun.

Do their houses look the same? Will Pietro’s new house look like this? As the family reached their home, Alberto Giocomin came into view, shivering outside without his coat. Nina realised she hadn’t seen him at church either.

“Adelasia, thank God!” He tossed up his arms, hurrying to Nina’s mother. “I ran here. Lucia is ready to have the babies.

Can you come?” His round face was creased with anxiety as he spoke to her mother. “Sì, ” she assured him. “It’s early, but with twins, this happens.”

Lucia Giocomin had grown an enormous belly with two babies inside her, but the rest of her body was stick thin, which made her appear wobbly. Nina felt sorry for the woman every time she saw her at the fountain fetching water. Adelasia turned to her husband and children. “I’ll be back after supper.” She nodded at Corrado. “No need to wait for me.”

Without pausing for his response, she rushed into the house to grab her ostetrica bag and within moments her sturdy frame passed Nina at a half-run with Alberto at her side. Nina watched them as a little of her fantasy for the Sunday afternoon fell away, knowing that her mother would not be there. She listened to the pair’s footsteps clapping on the stones down the Via Calzen until Nonna Argenta shook her from her thoughts. “Always putting other families first,” the old woman muttered in her crackly voice. “It’s no wonder…”

Her cackling trailed off and Nina broke in, imitating her mother’s certain tone and straightening her shoulders as Adelasia had when she spoke to Corrado.

“The polenta is already made,” Nina said, stretching herself taller in what she considered an adult way. “And I can make the sauce myself. Mamma taught me, for times when she has to be away.”

They ate polenta with sauce made from tomatoes grown on their terraced patch of land along with delicious hot-baked cheese from the milk of a goat they kept across the yard. The creamy flavours warmed them as much as the heat from the stone oven.

Although she was proud of the Captain’s status in town and appreciated it afforded them many niceties other families could not afford, Nina couldn’t help but look over at the empty seat where her mother belonged. When her younger sisters began fighting at the table, she scolded them like an adult.

They’d almost finished eating when Antonio plodded down from the attic where he and Vante slept next to dried corncobs and husks stored for the fire. He brought a stack of them down with him and threw some into the flames before he sat. Then he ate his supper, staring into the dancing heat, and returned to the attic straight afterwards, without saying a word. Nina frowned, thinking of his absence from Mass, his absence from their family today. He was never this quiet.

After they finished their afternoon meal, Nonna Argenta sat on the bed she kept in the sitting room behind the stove. The autumn sun descended early, and the house was dark except for the glow of the fire. Shadows flickered around Nonna while she knitted, happy to rest while Nina, Onorina and Vante cleaned up. The little ones had retreated to the girls’ bedroom upstairs to play. Corrado had gone up to speak with Antonio.

All work finally done, Nina found her book, still in the place she had left it that morning, and slipped into the sitting room, plonking down in the cushioned rocking chair. As she arranged herself, she was careful not to get too close to the fire whose embers snapped and sent specks of gold into the air.

Warmth flooded the room, and the lingering scents of their recent meal infused the room with comfort.

Nina opened the book to the page where she’d inserted a prayer card of the Blessed Virgin to mark where she left off.

After the first sentence, her older sister glided into the room, interrupting her reading. Nina couldn’t help but peek over her book to study Onorina, who sat across from her on the sofa, sewing. Everyone acknowledged Onorina’s beauty. Her black hair escaped its tie in curls around her face, framing her dark eyes. Unlike Nina, whose body was one long line, Onorina, now fourteen, had grown elegant curves. Even her stitches were graceful. Nina studied her own awkward hands at the end of skinny wrists. Graceful she was not. Of course, Nonna had tried to teach her to sew, but she was never good at it. Even a simple bag she made as practice had turned out so misshapen, they had cut it into rags for the outhouse. She sighed. At least I can make sauce.

Her mind drifted back to the announcement at church.

The latest emigranti. What if Onorina left for America like Pietro Pante? Don Segala said the men would work in coal mines; if Onorina went, she couldn’t do that. What could she do? What else is there? Nina put her book down and walked past her sister, through the kitchen and out the door, stepping outside to stand in the patches of grass the frost had not yet claimed.

The contrast from the warmth of the house to the chill outside shocked her, and she was acutely aware of her surroundings.

Her breath shone in the cold air. Through the nearly bare tree limbs, she could see San Micel and the little castle. She stepped one foot at a time, turning around slowly. Mount Avena, long and continuing, then Mount Vallorca. The mountains encircled her and felt like walls closing her in from a world she didn’t know.

Copyright 2021 Jennifer Anton