In her early forties, Chandi Wyant’s world crumbled in the wake of a divorce and traumatic illness. Determined to embrace life by following her heart, she set out on Italy’s historic pilgrimage route, the Via Francigena, to walk for forty days to Rome.

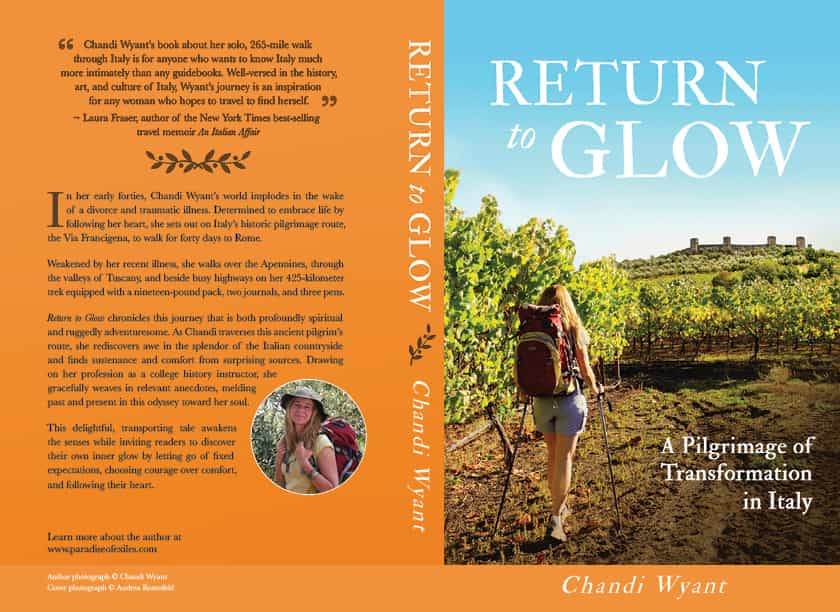

We had our book club with author Chandi Wyant on April 29, 2020 to discuss her book Return to Glow: A Pilgrimage of Transformation in Italy. Click here to watch the video. You can purchase a copy here but first enjoy an excerpt:

Chapter One: Lost

I’m limping on both feet—if that’s possible—in scorched wheat fields somewhere south of Siena.

I’m a woman alone and I’m lost.

The sun’s heat pummels the earth, and my limbs are like basil leaves, crushed by the stone pestle of the sun. Dusty tracks are scratched across the brittle fields. Sharp rocks push into the soles of my shoes, and I chide myself for bringing trail runners instead of day hikers with thicker soles. My spine is slimy against the pad of my pack and my teeth clench at the pain in my feet.

A farmhouse comes into view, suggesting a greener, shadier route to come. When I reach the farm, the trail disappears. I shift my weight from one foot to the other, trying to relieve their ache, wondering which way to turn.

The sound of a motor causes me to look toward a field where a man on a tractor waves me over. As I walk closer, he calls out, “Devi tornare indietro!” (You have to go back.)

I call to him, “Ma quanto indietro?” (But how far back?)

“The signs are incorrect! Go back!” I hear his shouts in Italian as he plunges the tractor into chunks of earth and rumbles away.

I return slowly on the dusty tracks to the brittle fields. Finding a handkerchief-sized patch of shade, I take off my pack and sit on it. My head drops toward my feet. Silence reigns, as if in the piercing heat even the crickets and birds have been struck mute.

I’ve been walking alone for twenty days, crossing the Apennines, climbing the hills of Tuscany, and skirting the edges of busy highways, and I’ve not been lost until now.

Lost. That’s why I undertook a pilgrimage in my favorite place in the world. In the past year, my foundation had been swept away by both a divorce, the pain of which surprised me, and a sudden traumatic illness. These ordeals left my physical and emotional health in such a terrible state of disrepair that I feared I would never get my glow back.

I lift my head from my hands. The silent, brittle fields offer me no solution.

I must not fail. If I fail at this, I will fail to get my glow back.

I’ve made myself a promise with this pilgrimage. Un voto, a vow.

Slowly, I stand, heave my pack on, and begin retracing my steps. My legs feel as if they cannot manage the weight of my body. Sweat threatens to drip into my eyes, and I stop to squint at furrows in the field—mini trails made by mice. Then I see a tractor track on a hill above me. I aim myself toward it. A tractor track will surely lead to a farmhouse at some point. Deciding on a direction brings relief, but I make slow progress. “Please,” I murmur to the sun, “you don’t have to keep pounding me.”

I hunker under my hat, my eyes cast downward, my shoulders cringing. Just put one foot in front of the other and you’ll arrive somewhere, I tell myself.

You’ll arrive somewhere.

Arrive. From the Latin ad rīpa, to the shore.

Am I getting there now, to a new shore?

Chandi arriving at Bagno Vignoni

Chapter Two: Pericolo di Morte

The decision to walk over four hundred kilometers (more than 250 miles) alone from northern Italy to Rome did not begin with the divorce. It began with the emergency surgery, which happened during a vacation in Italy just before I filed for divorce back in Colorado.

I was in my early forties and had been separated for a year when I went to Italy (a country I’d been returning to frequently for over twenty years), hoping to get rejuvenated and come back fortified, less in grief, more shored up, and ready to face the divorce process.

Two days into my trip, I was at my friend Sydney’s apartment in the historic center of Florence when I was struck by nausea, vomiting, pain in my abdomen, and fever. It was Sunday morning and the doctor who made the house visit said I had a virus. By Monday night I was in the emergency room at the hospital of San Giovanni di Dio.

“You’re awake,” the anesthesiologist says. I try to follow her Italian through my anesthetic haze.

“It was.” She uses a word that stays with me: bruttissima. Horrendously, disgustingly nasty.

Whatever it was, it was bruttissima, and that’s all I know. Days pass before I grasp how close I’d come to dying in that hospital seven thousand miles from home.

I’m wheeled into a large room that contains five other beds with five other urgent care patients. I can neither move nor eat.

Chandi with nuns in Sutri

When I see my oddly distended and bloated stomach, I think of the naked woman in Giotto’s Last Judgement who cowers under the clutches of a hairy blue creature. She’s a medieval product, before painters studied anatomy, and her distended pouch of a stomach is where her mons pubis should be.

If whatever happened didn’t kill me, surely the pain I’m in will. My reflex to deal with the pain is to pull my hair. That’s all I do for days when I’m not asleep—yank at my hair. My fingers have a will of their own, scouring my skull, seeking more hair to pull, like an invertebrate scouring the bottom of the sea in search of algae to consume.

When Sydney visits, I don’t know if I’ve been there two hours or two days. I sense she’s telling me what happened, but I can’t comprehend her words.

“Half an hour more and you would have died,” the surgeon tells me on the one occasion he comes to my bedside a few days later. “It was really acute. One of the worst I’ve seen. Why did you wait so long?”

I try to sort through his Italian words. Half an hour?

My mind is like a lane in a bowling alley, his words hurtling through it, knocking over the remaining few pins. I gasp as the last smidgen of stability is knocked away.

“Peritonite acuta,” he says, providing me with a two-word diagnosis.

My brain moves the second word to the front. acute peritonitis. But the words aren’t familiar, even in English. Or perhaps my brain is too strung out from pain and drugs.

When Riccardo the nurse struggles to find a vein in my arm to change my IV, I ask,“Cos’è peritonite acuta?”

“Arg! Your veins are so small!” he says, taking another stab. My breath jumps in my throat and I avert my eyes, focusing on Lolle, one of my roommates. Every night when she starts her hollering, two nurses march in like a SWAT team and tie her arms to the bed.

“Acute peritonitis. Fatal if neglected.” Riccardo snaps the words, and I think of a martial artist snapping a board with the side of his hand. “Ruptured appendix. Walls of the abdomen inflamed. Deadly bacteria. Sepsis.”

Days turn into weeks. Round green bruises grow on my thin arms, my feet swell, and a blinding pain develops daily in my head. Sometimes someone gives me a damp cloth that I hold to my forehead for hours in a daze as loud family members visit other patients in the room. At night, the bedpan is left too long by busy nurses and I sleep with it pressing into the flesh of my bottom.

Then I realize I’m having trouble breathing.

“You’re just nervous,” the doctor tells me.

I repeat myself for two more days.

A pulmonologist comes and sticks a gigantic needle in my back. “You’re coming with me,” he says.

To Heaven? I almost voice my thought.

The only clear thought I have is of my grandmother saying, “The train is leaving. Don’t be late!” when she was in the process of dying.

Pneumonia has developed, perhaps because of the sepsis in my lungs. It is a brutal setback, filled with more pain.

Author, Chandi Wyant

Four weeks after the surgery, I fly home. United Airlines refuses to change my return date in spite of the doctor’s letter to them stating I’d been in pericolo di morte—danger of dying. I change planes in Chicago and the wheelchair awaits. I almost cry with gratitude as the assistant wheels me through customs, onto the train between terminals, and to the gate.

On the jet bridge in Denver, my carry-on at my feet and my back feeling the hot Colorado air through the thin wall, I watch the other passengers pass by until no one remains except the flight crew. Trembling like one of those skinny hairless dogs, my eyes plead with the vacant jet bridge for the requested wheelchair to appear.

The flight crew begins to pass me.

“Can you help me?” My words whisper from white lips to a female flight attendant.

She pauses and looks at me perplexed.

I point limply to the carry-on at my feet. “I can’t lift it.”

She picks it up and slows her pace to match mine. I want to lean on her, this stranger I don’t know.

It’s a portent, I think, of how much I’ll have to lean on others who have no commitment to me. I’m far from family, and my divorce awaits.

You’ve read the first two chapters, now read the whole book, and join us on Facebook Live with author Chandi Wyatt on April 29th!