This article originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Dream of Italy.

You can also watch a video of our Facebook Live chat with Laura Morelli, PhD who wrote this article and our entire special report on the Etruscans.

In about 750 BCE, the people of central Italy had a problem.

To their south, ships carrying strange soldiers, merchants, and citizens were landing in the peninsula’s port towns. It was a time of expansion and colonization across the Mediterranean, especially for the ancient Greeks who were seeking apoikia—“homes away.” The island of Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula seemed like the perfect spot.

With the arrival of these new colonists, the disparate tribes of prehistoric Italy—each with its own language and customs—realized that the newcomers wanted the same things they did: fertile land, security, and viable trade routes. Colonization—and conflict—became a catalyst for cultural change.

From this time of transition, one group emerged with a distinctive culture that would persist for some 700 years—the Etruscans. From the 8th century BCE onward, many Etruscan works of art seem to answer the question: Who are we, and how are we different from them?

Are they really mysterious?

Countless books, courses, and documentaries center around the theme of the “mysterious Etruscans.” Historians have fueled this concept of the Etruscans as somehow difficult to understand or interpret.

The truth is that we know a lot about the Etruscans—even more than we know about many other cultures of the ancient Mediterranean.

The Etruscans formed a linguistic and cultural group occupying a swath of central Italy stretching roughly between Campania to the south, and the Po River in modern-day Lombardy. The name “Etruscan” formed the root of the word Tuscany, and the Greek word for the people of central Italy, tyrennoi, gave the name for the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Etruscan wealth came from fertile soil and an abundance of metal ore. They consolidated their people around hilltop city-states, and formed loose alliances with one another, but they were never fully unified.

The Etruscans were the first city builders of Italy. They founded cities that became Bologna, Pisa, Siena, Orvieto, Pompeii, Capua—even Rome in its earliest state.

What did the neighbors think?

Ancient Greek and Roman writers were fascinated with their neighbors to the north, and wrote a lot about them. These ancient writers tell us that the Etruscans were farmers and artisans, builders, sailors, and merchants. At the same time that Etruscan pirates were renowned for cruel treatment of their enemies, their priests were esteemed for a deep knowledge of the spiritual world.

These contemporary writers tell us that the Etruscans were noted for their wealth, their feasts, and for an unbridled enjoyment of earthly pleasures. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, writing in the late 1st century BCE, sums it up by saying that the Etruscans “were a people with customs unlike anyone else.”

So, if we actually know a lot about the Etruscans, then why are they considered mysterious? The legend of the mysterious Etruscans persists, I think, because of the two main questions that have occupied historians the most: Where did they come from, and what’s the deal with their strange language?

Find out even more about the Etruscans in our May issue of Dream of Italy, completely devoted to this topic:

For some two thousand years, people have offered theories about the origins of the Etruscans, whom they recognized as a distinct and separate cultural group. (Spoiler alert: They are not likely to have been extraterrestrials, as some have claimed!)

One theory is that the Etruscans originated in Asia Minor. The Greek historian Herodotus first wrote down this idea, arguing that the Etruscans came from Lydia, an area of modern-day Turkey. This idea that the Etruscans had migrated centuries before from Lydia was something that the Romans continued to hang onto and repeat.

The opposing theory, espoused by another Greek historian, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, was that the Etruscans didn’t come from somewhere else, but rather, were native to the land of central Italy.

Most recently, scientists have brought DNA testing to bear on this centuries-old debate. Testing of Etruscan burial remains seems to support the claim that the Etruscans were native to central Italy.

However, their origin has not been conclusively solved, and I imagine that this topic will continue to engage Etruscologists for some time.

Why is their language so strange?

I think the other reason why the Etruscans are called mysterious is because of their language. The Etruscans spoke a non-Indo-European language that remains unique in the world, unrelated to the ancient dialects of the adjoining regions.

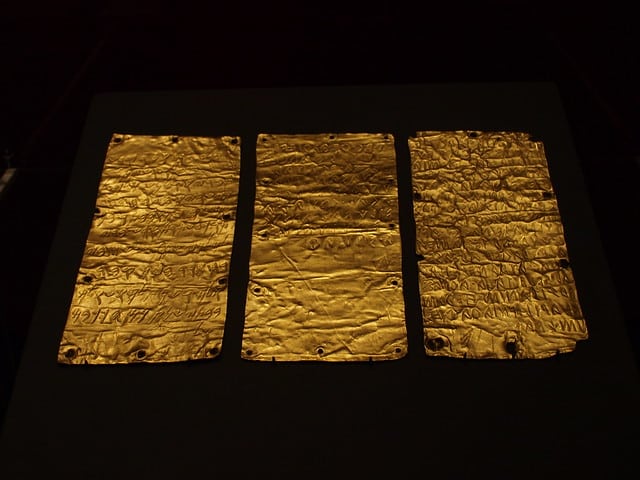

From the 8th century BCE onward, we have evidence of the Etruscan language in written form. There are some 13,000 existing texts in the Etruscan language, mostly inscriptions on stone or metal, or painted on pottery. Most of these texts come from funerary or religious contexts.

The good news is that modern historians can read these texts. The alphabet adopted by the Etruscans derived from the Phoenicians, and was widely read across the Mediterranean. It wasn’t the characters but the grammatical structure and use of the words that were unfamiliar.

The bad news is that the surviving texts shed light on a very narrow slice of Etruscan culture. They tend to be short and uninformative, mostly simple dedications or names.

So, although it’s inaccurate to say that the Etruscan language is “mysterious,” it’s true that the language itself only takes our understanding of the culture so far.

How do we know anything?

It’s important to realize that nearly any shred of Etruscan material culture that exists today was found underground. In this respect, studying the Etruscans is similar to studying the ancient Egyptians.

Etruscan cities—including Bologna and Pompeii—as well as smaller towns like Tarquinia and Volterra—continued to be built over and used over the centuries, so very little monumental architecture or city planning from the Etruscan era is there for us to observe.

On the other hand, there is a great wealth of many other types of objects—pottery, gold, metalwork, and other treasures. However, we have to bear in mind that the vast majority of objects that survive were found in a funerary context. It is from this culture of the dead that we do our best to interpret the culture of the living.

I believe that art opens a special kind of window on the past, and gives us a way to visualize what a group of people valued, what they loved, what they wanted to last.

By looking at Etruscan art and material culture, we can learn quite a bit about their language, their religion, their ways of dressing and adorning themselves, and how they lived.

Etruscology is a relatively young field compared to the study of ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. There are more questions to be answered, and much more to be learned.

In addition, new tombs and archeological remains turn up across central Italy on a regular basis. That means that Etruscan culture will continue to be a vibrant, lively topic. While we know much about the ancient people who inhabited Italy before the Romans, I believe that there are exciting finds out there just waiting to be discovered.

What about the ladies?

“Etruscan women are expert drinkers and are very good looking,” the Greek historian Theopompos of Chios tells us, writing in the 4th century BCE.

He goes on to give even more tantalizing details: “They take particular care of their bodies and exercise often. It is not a disgrace for them to be seen naked. Further, they dine not with their own husbands, but with any men who happen to be present.”

It seems that Etruscan women were distinct among the cultures of the Mediterranean. I wondered what made them special, so I went searching for answers…which I have turned into an online course about Etruscan women. Join me, art historian Laura Morelli, for a free online lecture about Women in Etruscan Art. Register at www.lauramorelli.com/EtruscanWomen.

What happened to the Etruscans?

The short answer is that they were assimilated into Roman culture—through means both peaceful and violent—over the course of several hundred years. Yes, the Romans overtook them, but in return, the Etruscans contributed much to Roman culture. Many of the things we consider purely “Roman” were pioneered by the Etruscans, including paved roads, the toga, the arch, and the concept of portraiture.

The Etruscans even drained the swamp that would become the Roman Forum, and built a temple on the Capitoline hill. In short, they made Rome a city—an Etruscan city!

— Laura Morelli

Laura Morelli is an art historian and historical novelist with a passion for Italy. She holds a Ph.D. from Yale University and has taught college students in the U.S. and in Rome. You can find more about what to bring home from Italy in her guidebook series, including Made in Florence and Made in Italy. Learn more about these books, along with Laura’s Venice-inspired historical novels, The Painter’s Apprentice and The Gondola Maker, at www.lauramorelli.com Laura also offers an online course in Etruscan art, find out more at www.lauramorelli.com/etruscans.

Header photo is of the Sarcophagus of the Spouses at Villa Giulia in Rome.