This article originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Dream of Italy.

By the 6th century BCE, some of the richest burials in the Mediterranean world were located in central Italy.

Much of our knowledge of the Etruscans comes from the incredible troves of material goods yielded from this well-established funerary culture. It’s through tomb excavations that we have the greatest treasures of Etruscan art, and that we gain the most knowledge about the Etruscans themselves.

The Etruscan Necropolis

The Etruscan necropolis—or city of the dead—was a parallel universe to the city of the living. Many of these cities of the dead were extensive, laid out on a grid plan much like the Etruscan towns, with paved roads, sidewalks, and regular blocks. Just like a town, they grew organically over centuries, spreading out into ever wider zones as time passed.

Similar to the ancient Egyptians, the Etruscans seem to have conceived tombs as homes for their dead. They carved out structures of rock and volcanic stone—meant to last for eternity—and filled them with their most valuable and precious belongings.

Inside each tomb, the bodies of multiple generations of one family might be collected. This practice set the Etruscans apart from the ancient Greeks and Romans, who buried only the immediate family together. I find this practice fascinating, since it shows that strong multigenerational family ties—such an important foundation of Italian culture—have very ancient roots.

Tomb Decoration

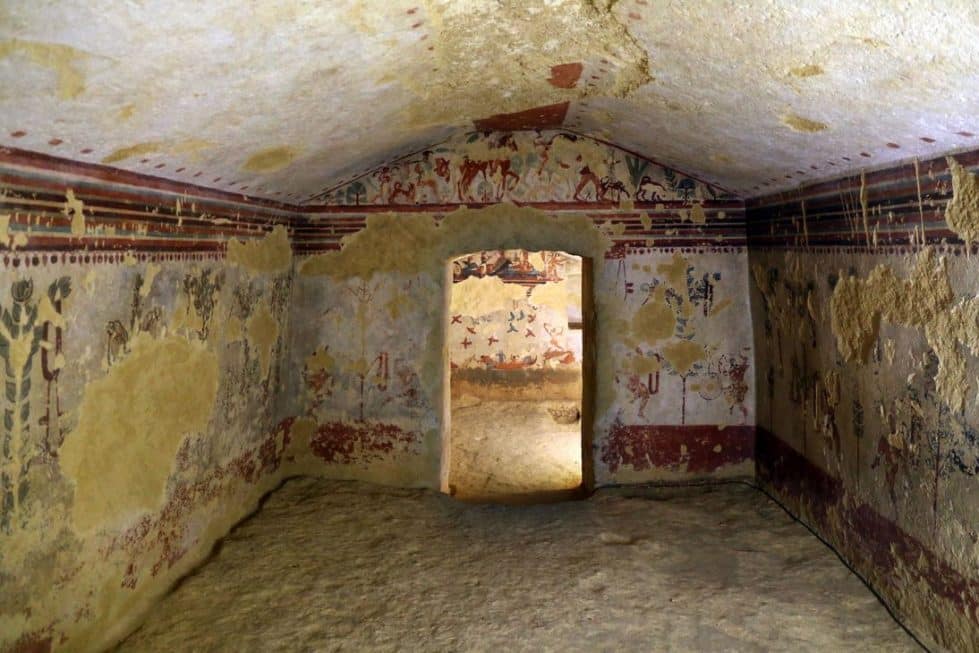

When you realize that the Etruscan tomb was designed as a house, it’s no wonder that they were decorated like one. Some tombs have realistic-looking ceiling beams, decorative columns, door jambs—even furniture—carved directly into the stone or volcanic tufa.

Based on the limited number of surviving tomb paintings, it seems that Etruscan painters had a remarkable ability to suggest that their subjects had a bright, tangible world just beyond the tomb walls. Many of the activities depicted in tomb painting might have been things the Etruscans carried out during funerary rituals: elaborate processions, games, contests, dances, animal sacrifices, ritual meals, and drinking parties. If so, then perhaps the paintings in the city of the dead carry on an eternal celebration of life that took place in the adjacent city of the living.

Toward the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, the Etruscans experienced confiscation of land and relentless Roman military victories. These threats and terrors must have seemed so insurmountable that they were inescapable even in death.

Symbols of the afterlife take on a fearful aspect; demons, serpents, and other creatures of the underworld appear on the scene. Gone are the images of the afterlife as an abundant banquet of earthly pleasures. Instead, the soul is locked in an eternal battle between good and evil.

Grave Goods

The Etruscan tomb was not only a repository for human remains. For more well-to-do families, the tomb became a treasure trove of luxury goods made over a long span of time, from terra-cotta cinerary urns and sarcophagi to fine works of gold, silver, bronze, and other media.

The family would then see these objects over and over again as they entered the tomb over the generations as they interred their dead. I imagine them handling beloved family heirlooms while they shared stories about those family members who had gone before them.

New Discoveries

Over the last 200 years, tens of thousands of Etruscan tombs have been documented. There continue to be discoveries of intact Etruscan tombs in the present day. A major Etruscan villa was discovered at Vetulonia in 2017, and in March of this year, the first major Etruscan settlement on Sardinia was uncovered.

We will surely see more exciting finds in the near future, so keep your eyes out for newly discovered Etruscan sites in the news!

Visiting Etruscan Tombs

In central Italy, Etruscan tombs are…everywhere! Once you learn how to spot them, you’ll be amazed that you’ve never noticed them, even if you are a frequent visitor to Italy.

And, while your friends are fanning themselves in the endless lines at the Colosseum and the Uffizi, you could spirit yourself off on an incredible journey to the quiet, nearly deserted necropoli of central Italy, where you can experience Etruscan culture firsthand.

Here are some places where you can take a deep dive, so to speak, into Etruscan tombs:

Cerveteri

Banditaccia Necropolis

Via della Necropoli, 43/45

Cerveteri (Lazio)

(39) 06 9940651

www.tarquinia-cerveteri.it

This city of the dead is one of the most spectacular remains of Etruscan civilization, named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This necropolis developed over the course of some 500 years, between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE.

As time went on, in addition to the large, circular, grass-covered round tombs known as tumuli, there were also squarish tombs constructed of hewn blocks and organized into regular units. Many of these tombs were not just reserved for the elite but were like middle-class neighborhoods. The tomb chambers were either partially or entirely excavated below the ground, some even hewn out of solid bedrock. The tomb structures have been mostly excavated so that it is possible to feel what it must have been like in Etruscan times.

The tombs themselves are organized along paved roads with gutters, drains, sidewalks cut out of rock, all representative of Etruscan urban planning. To walk the streets of Banditaccia, you get a feel for what it might have felt like to explore an Etruscan town.

Cortona

“Meloni” Etruscan Tombs

Località Il Sodo (Tuscany)

A short drive outside of Cortona into the village of Sodo, there are two Etruscan tumuli known fondly as “meloni” because of their melon-shaped domes. Though somewhat neglected, an impressively carved Etruscan altar is part of the attraction. Grave goods from these tumuli are now in the Etruscan Academy Museum in town, as well as in the Archeological Museum in Florence. Stop by the Etruscan Academy Museum or call ahead (39-0575-637235) to arrange a visit to the tombs as this site does not maintain regular opening hours.

Orvieto

Crocifisso del Tufo Necropolis

Località Le Conce

Orvieto (Umbria)

(39) 0763 343611

www.paao.it

This necropolis, a short walk out of town, contains a well-laid-out plan of tombs carved from the tufa rock that defines Orvieto. Many of the tombs have Etruscan names carved into the stones. The so-called Anello della Rupe path, an approximately three-kilometer path around the perimeter walls of Orvieto, affords beautiful views of the countryside and access to several quiet Etruscan tombs.

Tarquinia

Necropolis of Monterozzi

Strada Provincial Monterozzi Marina

Tarquinia (Lazio)

(39) 0766 856308

www.tarquinia-cerveteri.it

This necropolis is one of the only places in all of Italy where you can view painted tombs and gain an appreciation for the richness and color that might have adorned many other tombs now emptied.

The city of Tarquinia, located north of Rome, was one of the most important Etruscan towns. Along with the Banditaccia necropolis of Cerveteri, the so-called Monterozzi necropolis at Tarqunia is one of the treasures of Etruscan civilization.

Of the more than 6,000 tombs discovered at Tarquinia, fewer than 200 have surviving wall painting, an indication that perhaps only the wealthiest families could afford that luxury, or maybe that those are the only ones to survive the centuries.

Few and Far Between

Within Etruscan art, tomb painting is a special topic. Etruscan tomb paintings survive in a very narrow geography and context. About 180 Etruscan paintings are known; of those, 140 are from Tarquinia. Very few tomb paintings are found in the northern half of Etruria. The others are scattered across different cities and time periods.

Tomb Raiders

The Romans left Etruscan tombs largely undisturbed, but later cultures pilfered them–if they could find them or get into them.

The culture of amateur archaeology that permeated the late 18th and early 19th century started new quests to rediscover Etruscan-era tombs. Some of these “excavations” were less than ethical.

One of the most notorious tomb raiders was Luigi Perticarari, a Tarquinian farmer-turned-grave-robber who admitted that he personally emptied some 4,000 Etruscan tombs during his career, and eventually grew his illicit business within a complex organized crime network that included many middlemen and antiquities dealers. After he was prosecuted, he published an autobiography entitled I segreti di un tombarolo (Secrets of a Tomb Robber) in 1986.

— Laura Morelli

Laura Morelli is an art historian and historical novelist with a passion for Italy. She holds a Ph.D. from Yale University and has taught college students in the U.S. and in Rome. You can find more about what to bring home from Italy in her guidebook series, including Made in Florence and Made in Italy. Learn more about these books, along with Laura’s Venice-inspired historical novels, The Painter’s Apprentice and The Gondola Maker, at www.lauramorelli.com Laura also offers an online course in Etruscan art, find out more at www.lauramorelli.com/etruscans.