Editor’s Note: When I heard about the documentary film, Italy: Love It or Leave It, I wrote to my friend Rebecca Winke (an American expat in Umbria and a frequent Dream of Italy contributor) to see if she might want to watch it and write something for us. As always, she had some very eloquent thoughts about Italians (and expats) leaving Italy. Updated 2019.

Though it pains me to admit it, living in Italy has become increasingly disconcerting and disheartening over the past decade.

Disconcerting because Italy’s systematic dysfunctions–the famously impenetrable bureaucratic, financial, and political systems which have been looked upon by both Italians and the world with affectionate indulgence for half a century–have led to an economic decline which has had the country in a stranglehold for most of the past 10 years, with no sign of letting up. Though Italy’s antics were tolerated both internationally and domestically when the country’s economy was booming, now that the Bel Paese is increasingly under water, the world and Italy along with it are gradually waking up to how deeply the problems run.

Disheartening because Italy is emptying out. People are leaving, in waves and in droves. The first to abandon ship were the “accidental expats,” those foreigners who chose to live here for the “dolce vita” but were invested very little in the country itself. The second wave to strike out were the young, lesser educated Italians who headed abroad to work at pizzerie in London or pubs in Australia, leaving behind low paying jobs in Italy for low paying jobs in more exotic spots.

After these, the “invested expats”— those foreigners who had lived here for decades, had jobs and families and lives (and had paid taxes) here — began to leave, as they didn’t see any future for themselves or their dual-citizenship children in Italy. This has overlapped to the final and current wave of emigration: Italian professionals. These are older, educated Italians who are earning university degrees (on the taxpayer dime in this country of national university education) and taking them abroad, where they are able to climb the professional and economic ladder much faster than they would in stagnating Italy.

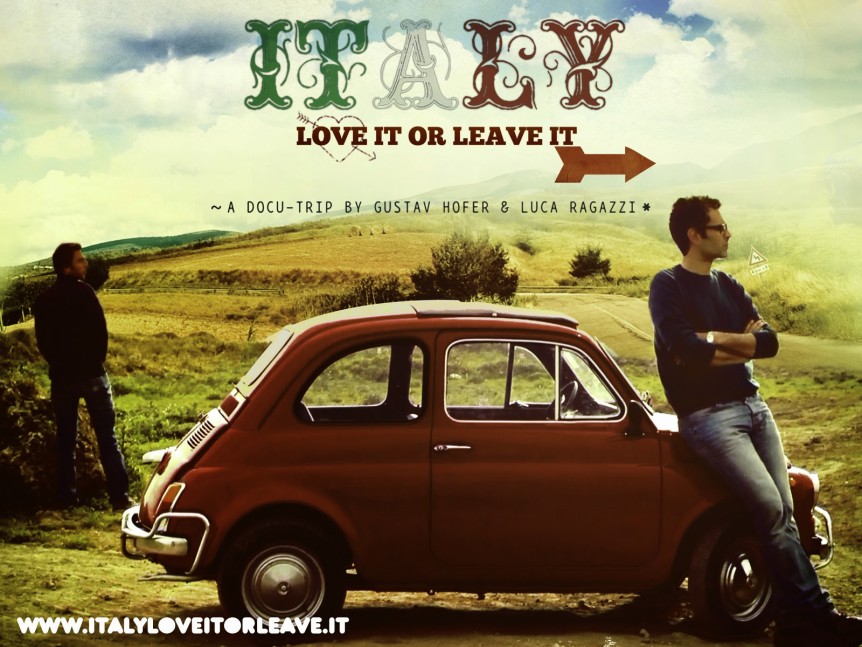

I have been most hit by these final two waves of exodus, as I have watched friend after friend, expat and Italian, give up on Italy and set off for a new life elsewhere. Italy’s new national anthem seems to be The Clash’s “Should I Stay or Should I Go,” and no friendly dinner, coffee, or cocktail is consumed without at least one refrain. The sadness of this emptying out (I refuse to use the antiseptic label of “brain drain” for a reality which involves so much tears and loss) and my own ambivalence about my future here after more than 20 years made me very approach/avoidance about watching the award-winning documentary

Italy: Love It or Leave It from 2011.

Here, 30-something Italian film makers (and real-life couple) Gustav and Luca have watched the departure of friends and family with growing consternation and, tiring of Italy’s “high cost of living, the lack of job security, the feudal university system, [and] generally reactionary attitudes and indifference to human rights,” and are beginning to grapple with their own decision about whether or not the time has come to say “arrivederci” to their homeland.

Much of the tension and conflict running through their discussions about whether to stay put or move overseas stem from a cultural subtlety often overlooked: Italy is a young nation, united just 150 years ago. Luca, Roman and culturally Italian, feels rooted in this country. Gustav, from Alto Adige and linguistically and culturally German, feels much less loyalty to his patria.

Their inner journey is charmingly and engagingly represented by an outward one, as they commandeer a series of an iconic Fiat 500s to road trip for six months down the length of Italy, stopping in a number of cities that form a backdrop for smart and often poignant in-depth looks at some of the biggest issues plaguing Italy today: mafia, corruption, the labor force, human rights, the environment. They do this by interviewing local activists, politicians, and journalists who frame these looming and often overwhelmingly complex problems in a more accessible context of personal anecdotes, small-scale campaigns, and community action.

The effect is a movingly accurate reflection of the confounding contradictions which make Italy both maddening and beguiling: immense, seemingly-unsolvable problems being tirelessly (and often humorously) chipped away at by passionate, dogged individuals. Indeed, Gustav and Luca’s road trip seems to be more about the journey of discovery itself, rather than an arrival at a cut-and-dried resolution.

They swing wildly between falling in and out of love with their country at every stop, demoralized by the issue while invigorated by the activist, taking viewers along with them on their emotional roller coaster ride. How can we throw our hands up in despair at the Mafia, when there is an Ignazio Cutrò willing to risk himself and his family to rebel against their power in his small Sicilian town? How can we roll our eyes at the degrading depiction of showgirls in Italian media when there is a Lorella Zanardo who spends her days in Italy’s public schools raising awareness? How can we give up on this country, which gave the world Slow Food?

Ultimately, this marginally hopeful sentiment is expressed movingly in the documentary’s final interview with Italian author Andrea Camilleri, who admonishes the young filmmakers that if they have any love for their country, any remaining affection or hope, then it is their duty to stay and fight for it. Anything less would be a desertion. Indeed — spoiler alert — the final scene reveals that the couple has decided, for the moment, to settle in Rome.

But, I had to ask myself, for how long?

If you would like to read more about the state of affairs in Italy, read this article from

The New York Times and this one from

Time.